Building internal government capability for policy – set expectations and build collective expertise

18 June 2024

● News and media

Governments across Australia and in Aotearoa New Zealand are looking to improve the quality of their advice to ministers and the capability to design and deliver it. This includes building internal capability through development and training and reducing the reliance on external consultants and contractors.

Both the Australian Senate and the New South Wales government have recently released reports on the use of consultants, including for policy development. Policy is, after all, usually considered core business for the public service. Reducing the reliance on external expertise or capacity requires governments to think about what skills are required for policy and how they can be developed.

ANZSOG Practice Fellow (Policy capability and public management), Sally Washington, has worked with a range of jurisdictions (including Australia, the UK, Ireland and Aotearoa New Zealand) to help improve their overall policy capability.

In this article, first published by Apolitical, Ms Washington outlines the importance of articulating the skills required of public servants in policy roles and why organisations and jurisdictions need to think beyond individuals and their skillsets to assess and build the capability of teams, organisations and the overall public service. She says this is part of building an effective policy infrastructure, connecting people development to the supporting models (such as the 5D policy model), frameworks, and toolkits that guide good policy processes, and improve overall policy performance.

Ms Washington argues that “Policy is a team sport not an individual pursuit” and that managers and leaders need to think about building the collective expertise of teams and organisations. Workforce strategies need to be built strategically by assessing “what skills are we going to need in future and how do we develop or recruit them?”. “Sometimes bringing outsiders into the mix to fill temporary gaps in expertise or capacity is entirely appropriate and cost effective”.

Setting expectations about the skills required of policy professionals and using them to build the collective expertise of teams, organisations and the overall public service is part of building a high-performing policy advisory system that supports good government decision making.

How do policy practitioners know what is expected of them? As the world gets more complex, so do the demands of policy advice and the skills required to produce it. Policy practitioners need to be familiar with a range of newer methods (user-centred design, behavioural insights, data analytics, use of AI) as well as being skilled in more traditional analysis (cost-benefit, regulatory impact analysis) and the advisory tasks (briefing notes, verbal briefings, Cabinet submissions) that are the bread and butter of a policy professional’s job. This means going beyond generic public service or departmental competency frameworks to see policy as a profession with a defined skill set.

Articulate policy skills

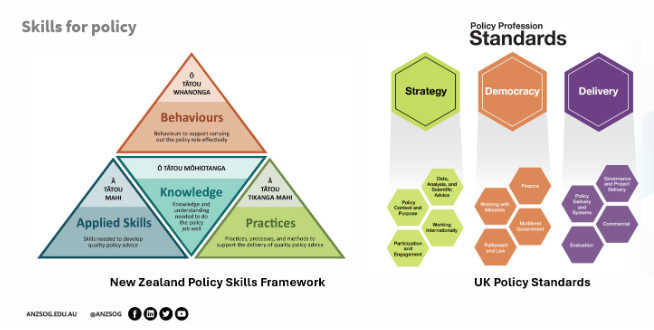

Aotearoa New Zealand and the UK policy professions have articulated the skills required of policy practitioners. The UK has recently upgraded its Policy Profession Standards which are supported by a curriculum and comprehensive certified training options, up to masters level. Aotearoa has recently revised its Policy Skills Framework to include responsiveness to Māori and to reflect legislative changes in the Public Service Act 2020. The UK standards are organised around types of policy work – strategy, democracy and delivery, while the NZ framework is more about knowledge, skills, behaviours and practices that can apply to any policy work. The Australian public service describes policy skills – strategy, policy and evaluation – as part of its ‘Public service craft’.

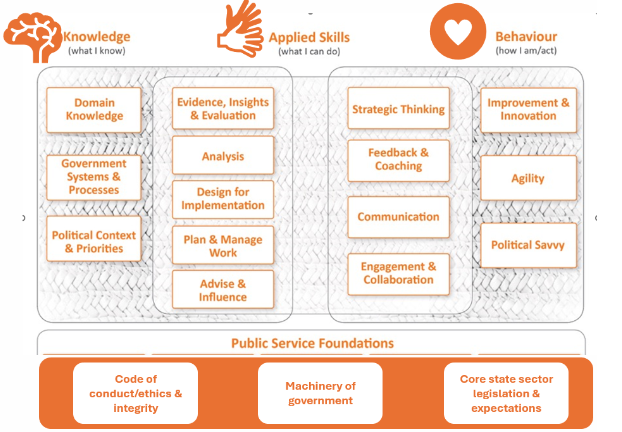

So what skills are required for policy? For this article I’ll revert to the original NZ Policy Skills Framework. It’s a simple and practical articulation of the skills policy professionals need for their day-to-day work, regardless of portfolio or jurisdiction. And it is highly transferable; it has been adopted elsewhere (for example, by the South Australian Department of Education). It includes knowledge (“what I need to know”), applied skills (“What I need to be able to do”) and behaviours (“how I need to act”). I describe this as engaging the ‘head, hands and heart’ in policy work. The skills cover domain knowledge (portfolio expertise); understanding government processes and priorities; analytical and advisory skills (use of evidence and evaluation, policy design that includes implementation and is well planned and managed); working with others (collaboration, engagement, communication) and having the right mindset (curious, agile, innovative and politically savvy). These are underpinned by generic public service foundations.

Figure 2 – Adapted from the original NZ Policy Skills Framework

Each policy skill can be described at different levels of expertise: developing (starting out); practicing (a safe pair of hands) and expert/leading (top of the game). While skills like “strategic thinking” and “political savvy”, have always been seen as critical for policy analysis and advising they are rarely described in a way that enables policy practitioners to assess their current level of expertise, or the expectations for getting to the next level.

Take strategic thinking as an example. A generic description would be that the person thinks outside the box and can incorporate longer-term thinking and broad system perspectives into their policy advice. A person who is top of their game would be able to lead work to set a vision and strategic direction to achieve longer-term outcomes, and translate that intent into medium-term plans and initiatives, including with some expertise in foresight. But a person just starting out would be just developing an ability to see how current actions contribute to longer-term outcomes and the synergies between policy issues, portfolios and government sectors.

Assess and build the skills – of individuals, teams, organisations

In comparison to the UK model which enables policy professionals to move up levels of policy expertise consistent with the curriculum and training offerings, the NZ model enables policy professionals to show both breadth and depth of policy expertise, on the understanding that one individual is unlikely to be highly skilled in all policy tasks. Indeed, an individual might be expert in terms of advising and influencing decision-makers but less skilled in planning and managing a portfolio of work (which is why career paths that shoehorn analytical experts into management roles, to progress up the ranks, can reduce overall performance).

Articulating the skills expectations of policy professionals offers a foundation for mapping the skills of individuals and teams and can be used in performance and development conversations, for training (“where do we need to upskill individuals or the team?”), for recruitment to specification (where a manager can identify and fill gaps in the team or organisation by collating the collective skills of the team ), and for workforce strategies (“what skills are we going to need in future and how do we develop or recruit them?”). I’m particularly interested in the potential to articulate policy archetypes (deep data expert, ministerial advisor, engagement specialist etc) and how those different policy personas come together to create a high-performing policy team. After all, policy is a team sport not an individual pursuit.

Create enabling environments to enhance performance

Policy leaders need to think about the make up of their teams and organisations. In managing their people, policy leaders and managers need to think about how to enable staff. This means offering staff opportunities to stretch and grow their skills and experience (most learning is done on-the-job), clarity about where decision rights sit, and avoiding overly hierarchical authorisation regimes (a handbrake on efficiency and a staff demotivator). Fair work allocation and maintaining balance across a team or organisation, ensuring the policy “stars” avoid burnout and less experienced staff get a crack at working on challenging, rewarding and skills-enhancing policy projects is also important. It helps if more senior staff take responsibility for guiding, coaching, and mentoring less experienced team members.

Enhancing the skills of policy professionals and the teams, organisations, and systems they work in requires some key things:

- Setting expectations about what policy professionals need to know and be able to do, and providing support for building policy muscle (especially on-the-job)

- Moving beyond a focus on individuals and career progression to think about collective expertise and how and by whom demands for policy work will be met now and in future

- Building people capability as part of wider initiatives or policy infrastructure to connect people development to the supporting models, frameworks, and toolkits that guide good policy processes to improve overall policy performance.

Highly skilled policy professionals working in high-performing teams in enabling organisations are an essential ingredient for a modern policy advisory system that supports good government decision making.

Sally Washington has written other articles on how governments can improve policy, including: Building policy capability, Building the infrastructure to support good policy advice, Fixing the demand side: how the public service can support ministers to become ‘intelligent customers’ of policy advice Hindsight, foresight and insight: three lenses for better policy-making | ANZSOG