How do we ensure ministers and their departments engage in the most productive way from the start of their working relationships? The Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) Director Aotearoa-New Zealand, Sally Washington, unpicks the dimensions of a great relationship between ministers and their departments, and how that might include supporting ministers to be more ‘intelligent customers’ of policy advice. This is the first in a short series of articles as part of ANZSOG’s efforts to promote good policy development.

Improving the quality of policy advice – and the capability to produce it - is on the agenda of many organisations and jurisdictions around the world. For example, Aotearoa- New Zealand’s Policy Project, and the United Kingdom’s Head of the Policy Profession unit are well established agents of change. The Delivering Great Policy program in Canberra has similar aims for the APS.

These are all important initiatives, but by exclusively focusing on the ‘supply side’ of the good policy equation we ignore a central problem. What happens when policy advice is produced but doesn’t hit the mark for the customer of that advice? What happens when that customer, the minister, isn’t able to articulate what they want to achieve, or can’t tell if advice delivered is telling the full story, or is good advice or not?

Few, if any, have done any complementary work on the ‘demand side’ of the ledger, on the role of ministers in ensuring they get quality policy advice and actively support improvements in public service policy capability.

Good government decision making depends on great relationships between ministers and their departments. Departments advise, ministers decide and departments implement, right? In reality, the equation is much more complicated.

We know that the public service no longer has a monopoly on providing advice to decision-makers, if they ever did. Ministers have multiple sources of advice, and this increasingly includes political and policy advisors in their own offices. Public service advisors are going to have to be best in class to establish and maintain relevance as trusted expert advisors. They need to be able to make sense out of the wealth of evidence and range of competing views (including from citizens and frontline colleagues) and be able to synthesise that complexity into their advice.

The policy ‘pre-nup’: setting some ground rules

Often new ministers come into the role thinking they have to have all the answers. Instead, they are likely to be more effective if they have the right questions. They need to be able to articulate their broad policy goals and know what they want to achieve. Confident ministers invite free, frank and fearless advice and are open to challenge and options about the best way of doing things. Great ministers invest time and energy in developing good relationships with their departments. They are skilled at getting the most out of the policy advice services available to them.

Not all ministers fall into the ‘great’ category however, and not all relationships flourish as they should. It’s important for public services to have processes in place to make those relationships as strong as they can be to ensure that ministers can make the most of their time in a portfolio, which might be limited.

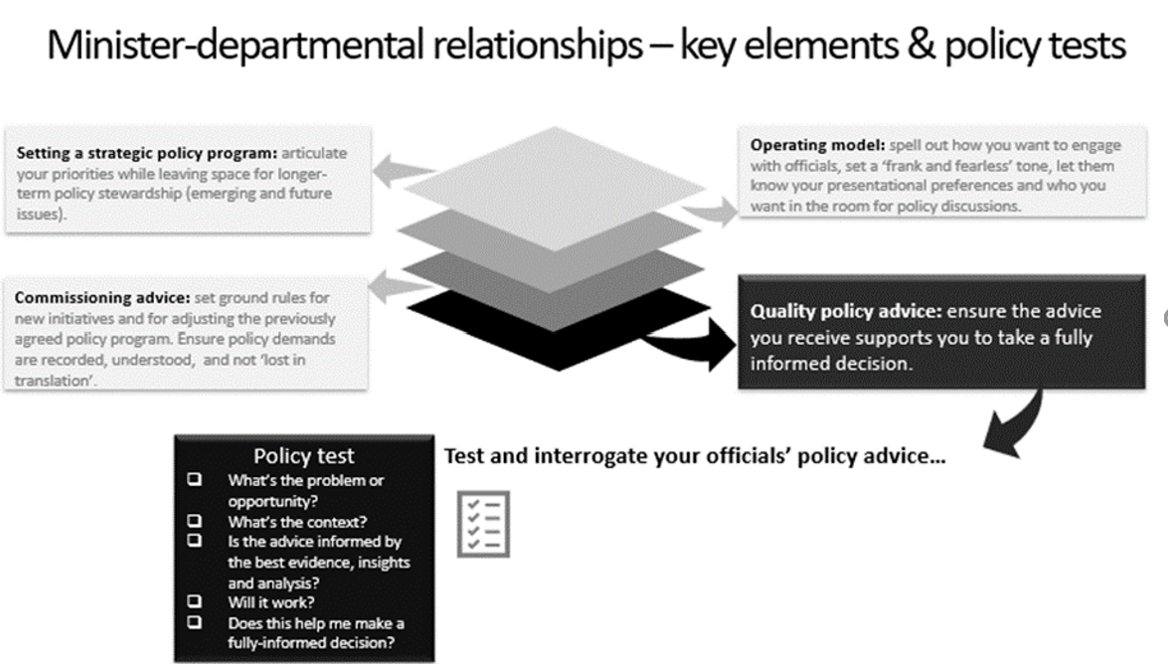

The start of any relationship is a good time to set the ground rules – the ‘policy pre-nup’. Having a framework for a discussion on those ground rules can help. An effective ministerial/departmental policy advisory relationship has several key dimensions (see diagram):

an agreed policy program – ministers need to articulate their policy priorities but also leave space in the authorising environment for longer-term policy stewardship (emerging or future issues) ground rules for commissioning advice – there need to be established ground rules for adjusting the policy program when circumstances change or new demands emerge – responding to COVID-19 is a case in point an operating model for engaging with advisors – they need to spell out how they want to engage with officials, to set a frank and fearless tone and to articulate their presentational preferences, processes for ensuring that advice delivered is of high quality – ministers need to be able to interrogate advice to make sure it stands the quality test and helps them take evidence-informed decisions.

Testing the quality of policy advice

As the customer of policy advice, ministers should be able to challenge and interrogate policy advice offered by their departmental advisors. Policy decisions are rightly the domain of politicians, but they can help improve the quality of the advice they receive, and the effectiveness of their own decisions by being open to frank and fearless advice and by being able to constructively interrogate the quality of the advice they receive.

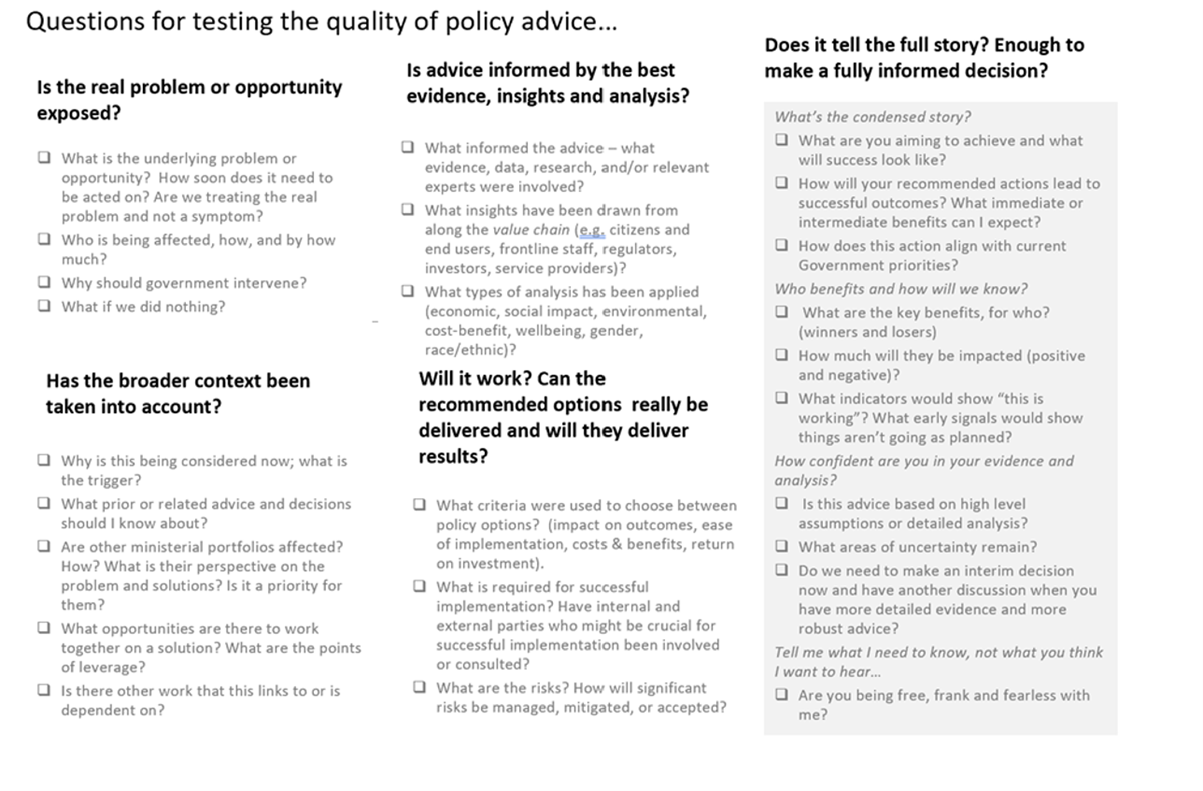

The questions in the ‘Policy Test’ box in the graphic above are designed to support ministers to test the quality of advice tendered - to make sure it tells the full story, is based on the best available evidence, includes the relevant context, can actually be delivered, and will deliver the expected results. More detailed questions are shown in the checklist below.

Ideally questions from the ‘demand side’ (ministers) should mirror agreed ‘supply side’ quality characteristics or standards that departments have set themselves. The questions are loosely based on the New Zealand Policy Quality Framework, which all government departments in Aotearoa-New Zealand must now use to measure and report on the quality of their advice to ministers. This could be adopted, adapted or replaced with a bespoke framework to reflect the particular priorities of a Minister or jurisdiction.

Developing some policy tests, either simple or detailed checklists, might support and enable ministers to be more intelligent customers of the policy services available to them.

Departments should also conduct regular ‘health checks’ to test overall ministerial satisfaction with those departmental advisory services so they departments can be reassured that they are providing the best possible service.

These tools will help ministers and departments build fruitful relationships in a context where ministers have access to other sources of advice, and may not always give priority to the public service view.

If both the ‘supply’ and the ‘demand’ side of the ministerial/departmental policy advice relationship have a common understanding about what quality looks like, and there are agreed overall priorities, then it is easier to have ‘courageous conversations’ about policy intent and how decisions get made and implemented. And that means better decisions for the public we serve.