Social impact bonds (SIBs) have gained popularity as an alternative financing method for public services. However, integrating private finance instruments into public accountability procedures is difficult. An article in the Australian Journal of Public Administrations examines those public accountability concerns. It identifies four accountability dimensions that need to be safeguarded: transparency, controllability, responsiveness and liability. The article is based on a review of the empirical SIB research and a literature review.

The SIB model

SIBs are ‘payment-by-results’ or ‘pay-for-success’ contracts that attract private investors to public policy domains such as social services. Responsibilities shift between the public and private sectors:

- Public goal-setting: A public agency sets a policy goal that calls for an innovative approach. Targets are formulated and quantified in terms of expected impact. Private partners are brought together to negotiate on targets, measurements, and pay-out clauses.

- Private finance and provision: During implementation, a ‘black box approach’ is followed. The service provider that chooses which interventions to make, while government control is limited. Investors provide the upfront capital to cover the costs of the project.

- Public outcome-based repayment: The investors’ return depends on the project’s actual impact. If the program exceeds expectations, the public agency pays out a return to the investors. When the intervention does not meet targets, investors are not compensated.

Public accountability framework

Public accountability in SIBs can be accomplished through four dimensions.

- Controllability. Delegating power to government agencies allows them to control the actions of other partnership actors, fostering direct hierarchical public accountability in arrangements like SIBs.

- Transparency serves as a foundation for accountability processes by making information publicly available.

- With liability, private actors can be accountable for their performance by linking financial risk to their actions.

- Public accountability can also be achieved when SIB projects show responsiveness to the direct expressions of public needs.

What the research found

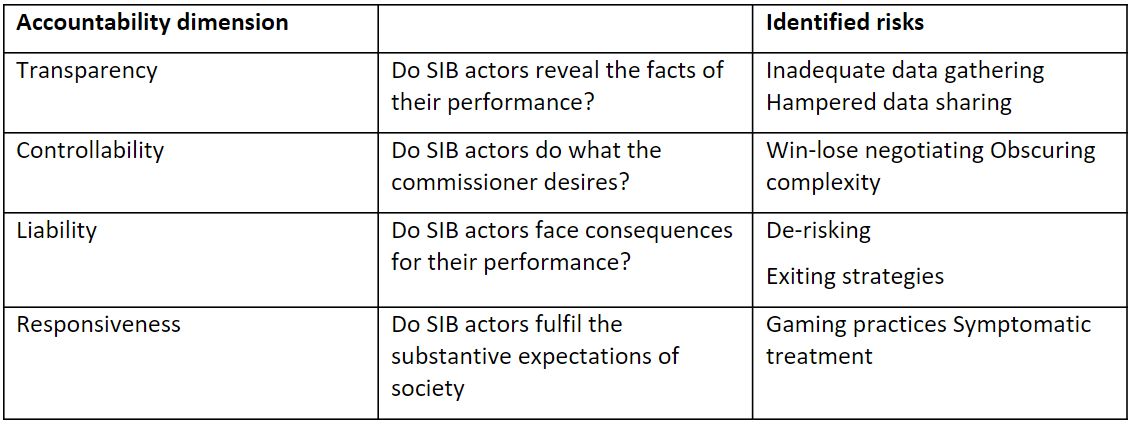

The review revealed the risks undermining public accountability in each of the four accountability dimensions, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Identified risks in the social impact bond literature

The risks explained

- Inadequate data gathering: The impacts of SIB interventions were hard to assess due to the poor validity benchmarking data and the absence of reporting standard. SIB evaluations often portrayed interventions as qualitative successes, even when no evidence could be found that beneficiaries were better off than a control group.

- Hampered data sharing: The dissemination of data to the public was not always guaranteed. There were also perverse incentives for withholding information.

- Win-lose negotiating: Twisted negotiations hindered public actors from designing SIB contracts in a way that full outcome-based control was attained.

- Obscuring complexity: Conflicting interests and organisational differences of the SIB partners can create a complexity in SIB contracts that makes them hard to oversee. There were losses in control due to the voluminous and multiple SIB contracts.

- De-risking: Investors actively strive to reduce the financial risks of underperforming projects.

- Exiting strategies: Liability is undermined when SIB actors manage to negotiate an early way out of underperforming SIBs.

- Gaming practices: Inadequately designed SIBs can be a playground for gaming practices. For example, beneficiaries that are already closest to achieving the outcome targets of the contract were given services, while the most challenging cases are left outside the cohort.

- Symptomatic treatment: Commissioning through SIBs risks directing policy interventions to a specific group of accessible beneficiaries or to easily measurable outcomes. The pursuit of quick fixes through SIBs oversimplifies the intricate underlying societal issues and their causes.

What this means

The article makes three recommendations for safeguarding public accountability:

- Incentives for mission drifts and gaming strategies can be suppressed when policy-making responsibilities remain the prerogative of the public sector.

- Effective platforms and arrangements for information collection, sharing, and management are instrumental to clarify the cloudy information flows between partners.

- The policy and budgetary purpose of using a SIB should consistently serve as guiding principles during its design. If room is left for risk-evading or gaming practices, SIBs not only lose their fundamental purpose of generating societal impact, they also shelter private actors from liability for inadequate contract execution.

However, the research shows implementing these safeguards while conserving the viability of the SIB model proves challenging. For example, prevent mission drift and gaming have resulted in SIBs becoming prohibitively time and resource intensive.

The article suggests that public agencies should employ SIBs cautiously, selecting the instrument only when direct funding of uncertain innovations would bring large financial risks. It also suggests that it is wise to convert successful programmes to more conventional funding without intermediaries or investors.

Want to read more?

At a cost: A review of the public accountability risks of Social Impact Bonds – Simon Demuynck and Wouter Van Dooren, Australian Journal of Public Administration, September 2023

This article is available via individual or institutional access through a library service such as a university library, state library or government library.

Each fortnight The Bridge summarises a piece of academic research relevant to public sector managers.

- Published Date: 8 November 2023