The question of how public sector agencies can best work together is central to tackling the most complex public policy challenges. Using a range of Aotearoa New Zealand case studies, a new e-book identifies 18 model forms for joined-up government. The book rejects the idea that collaboration can be reduced to a universal best practice and instead answers the question: when should you use which model?

The question of how government should be organised has long been central to the field of public administration. In the complex world of the twenty-first century, the most persistent problems facing public administrators span agency boundaries. This is partly the result of past successes, as more progress has been made on problems that could be addressed by agencies working in siloes. Consequently, the most pressing problems that remain are the ones that cross agency boundaries.

It is also the result of past failures. Some problems that governments thought could be solved in siloes are resistant to policy intervention. Governments now realise that progressing these less-tractable problems requires agencies to work together. Other drivers such as heightened interdependency and uncertainty feed into the increased necessity of collaboration.

Collaboration is frequently fraught and costly. Interagency collaboration consists of ongoing negotiation which has significant coordination costs compared to the efficiency of a simple hierarchy. Imperfect alignment of collaborative goals introduces the risk of some parties opportunistically pursuing individual goals. Even when collaboration is successful, the transaction costs tend to be high.

The New Zealand public service developed and adopted a Toolkit for Shared Problems. This is a two-dimensional framework that aligns different collaborative methods with problem contexts. Developed in 2017, the Toolkit is based on a stocktake of Aotearoa New Zealand’s experience with interagency collaboration from 2004 to 2017. It was revised in 2020 and incorporated feedback from the first three years of implementation as a design tool.

The Toolkit is framed around three clusters of problems:

- those requiring agencies to collaborate to achieve a public policy objective

- those requiring agencies working together on common functions, processes or professional disciplines

- those requiring agencies to work together to deliver more aligned or joined-up services.

The idea of ‘trade-offs’ was used to differentiate the various experiences of collaboration. The more that agencies needed to sacrifice, the more formal the powers and accountabilities needed to be. This led to the development of a two-dimensional framework: the type of problem on the vertical axis and the required degree of trade-offs (and therefore formal accountability) on the horizontal axis. This is depicted in see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Framework for contingent collaboration

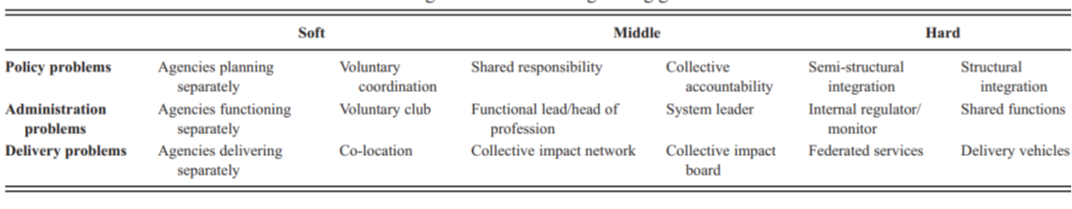

Six different collaborative models were identified for each problem type, making a total of 18 models. These range from ‘soft’, informal or voluntary models to ‘hard’ structural reorganisation. The 18 models are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Collaborative models

For public service practitioners, the Toolkit is heuristic to understand an unstructured problem and order it into a framing structure that will maximise opportunities to address it. Based on the problem context, practitioners need to decide how far ‘down’ and then how far ‘across’ the Toolkit would provide the most promising solution.

The models described in the Toolkit are ‘ideal types’ rather than being prescriptive or rule based. The Toolkit is flexible and can be applied differently throughout the life cycle of a collaborative initiative. For example, the easiest improvements may be achieved using ‘softer’ models, but later improvements may involve agency sacrifices and require ‘harder’ governance models.

Some problems are best conceived of and addressed as a collection of related or nested elements. For example, a ‘hard’ model may be required to achieve a carbon-neutral public service, within the context of a broader (soft) voluntary collaboration around issues relating to environmental management. Some problems operate at multiple levels, for example, requiring policy agreement at a national level as well as collective action at a frontline level.

The bottom line

Effective collaboration is not premised on a single approach. Distinct contingent solutions are required for different problem contexts. The behavioural and social disposition of actors is also a key determinant of collaborative success. The case study examples showed collaboration was most successful when public servants:

- understood the purpose or goal of the work

- judged this goal as worthwhile

- felt that their actions were instrumental in achieving that goal

- believed that others would sustain effort towards the goal for long enough for the collaboration to be successful.

Want to read more?

Contingent collaboration: When to use which models for joined-up government - Rodney J. Scott and Eleanor R. K. Merton, Cambridge University Press, June 2022

The e-book is available via institutional access through a library service such as a university library, state library or government library.

Each fortnight The Bridge summarises a piece of academic research relevant to public sector managers